Introduction

When we choose to live an iterative life, how do we know which changes are worth keeping? Personally, I rely on data, subjective or objective, to evaluate which experiments are most impactful.

Take my Colemak/split keyboard experiment as an example. My goal was to find a typing method that would be easier on my body and more efficient. The data I collected was largely subjective: How did my wrists feel by the end of the day? Was my back less fatigued? Even this kind of data can be helpful in deciding which experiments are worth keeping and which should be abandoned.

I believe many experiments fail because we lack a clear way to interpret the data we're receiving. How can we tell if we're improving? If we don’t define that metric, isn’t it easier to just revert to the old way?

In this post, I’ll share a framework to help you design and track your own life experiments in a way that yields helpful feedback. First, a key principle: experiments should be tiny and iterative.

The 5-Step Framework

Step 1: Define the problem or goal

You can’t start an experiment without a clearly defined problem or goal. This becomes your "why"—the rationale for the experiment. To keep things small and iterative, try to make the problem as specific as possible.

Step 2: Form a testable hypothesis

Now that you have a goal, you can form a hypothesis. Think of it as a theory: If I make this change, what do I expect to happen? For example, I hypothesized that switching to a split keyboard and new layout would reduce my hand and back discomfort.

Step 3: Choose metrics and a timeline

How will you measure the impact? This is where both objective and subjective data come into play. You might track sleep hours, mood, pain levels, or screen time. You'll also need to decide how long to run the experiment before reviewing results. Some changes yield quick feedback; others require longer observation to reveal patterns.

Step 4: Execute with discipline

Measurement requires consistency. Without it, you risk losing the data needed to make a decision. You don’t have to be perfect—but you do have to be deliberate.

Step 5: Analyze and iterate

At the end of your experiment, review your data. What worked? What didn’t? And more importantly: Is there an opportunity to iterate? Rather than labeling the experiment a success or failure, consider how small adjustments might improve outcomes.

Tools and Tracking

I keep my tracking setup simple. The last thing I want is for data collection to become a source of friction. I use tools like Oura, Garmin, and Apple Health—platforms that already provide feedback on my health and behavior.

In the past, I tried exporting this data into spreadsheets or visualization tools. But for me, the time and effort often outweighed the benefits. So now, I mostly rely on the insights available directly from these platforms.

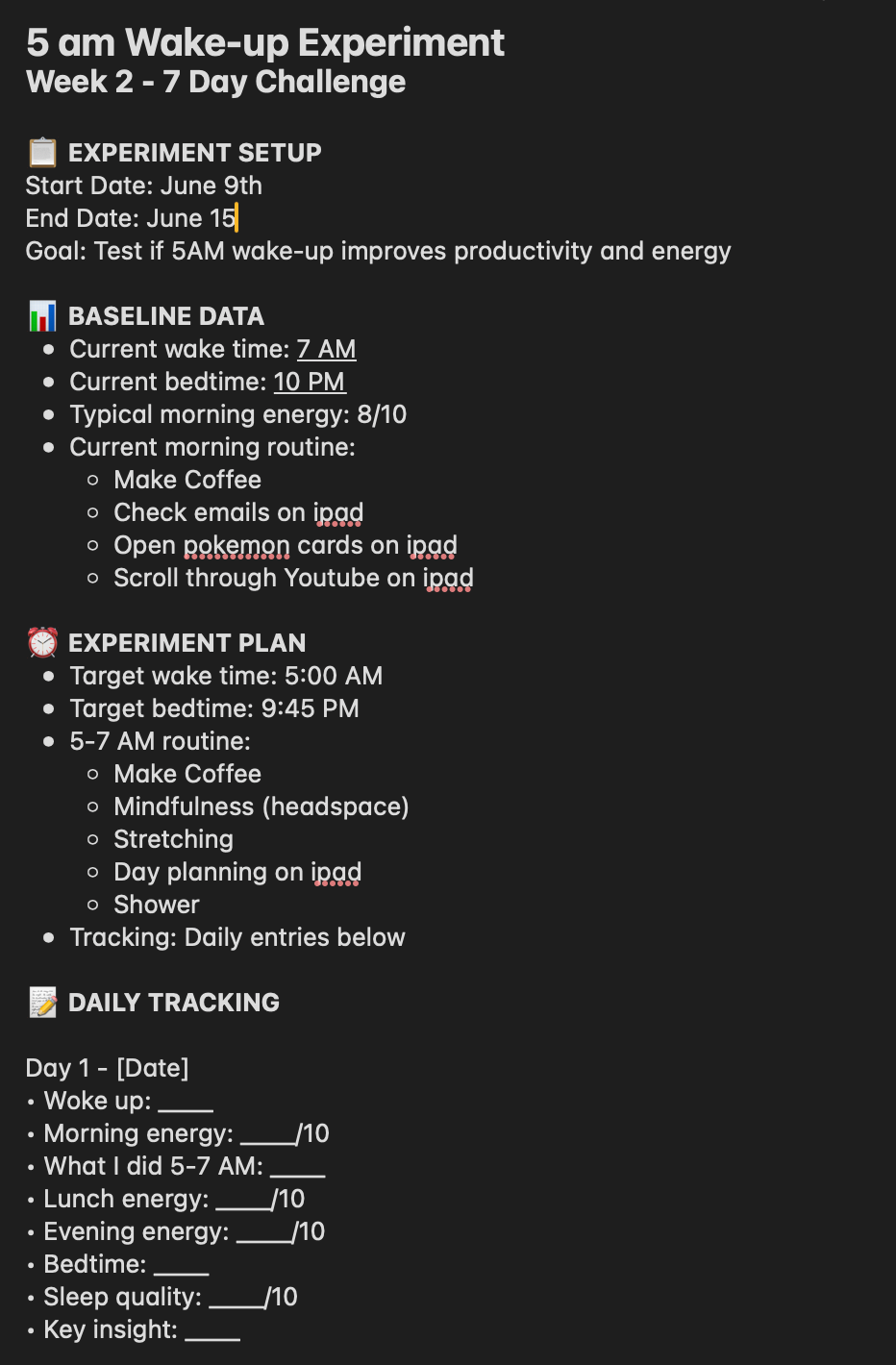

That said, I do like to pull relevant metrics into my experiment tracking notes. Currently, I store these in Apple Notes. Here's an example of how I lay out an upcoming experiment:

Common Pitfalls

Before you dive in, let me share a few lessons from my own missteps:

1. Running too many experiments at once

It’s tempting to stack experiments, but this can corrupt your data. If you're testing sleep efficiency and simultaneously testing a new supplement that also affects sleep, how do you know which change caused the result?

2. Inconsistent tracking

Skipping data collection—even for a day or two—can leave gaps in your dataset. Those missing points can introduce misleading outliers and make your conclusions less reliable.

3. Quitting too early

Every experiment has an adjustment period. The early days often come with friction—physical discomfort, mental resistance, or other stressors. If you end the experiment too soon, your data may reflect that temporary discomfort rather than the actual long-term effect.

4. Ignoring qualitative data

With personal experiments, how you feel matters. Even if the quantitative results suggest success, if a change brings anxiety, frustration, or exhaustion, it’s not a clear win. Your subjective experience should always be part of the analysis.

Getting Started

Now it’s your turn. Start with a small experiment that allows for an easy, iterative change. Choose something that can be tested over a short time frame so you can practice the process without feeling overwhelmed.

Here are a few experiments I recommend, based on my own experience:

- Try a split keyboard. Especially if you find that traditional keyboards force you to hunch or roll your upper back, this can be a game-changer.

- Quit alcohol. With so many great non-alcoholic alternatives, this is easier than it used to be. For me, the impact on my sleep has been profound.

Get started today, and follow the process step by step. Let me know if you have questions or need advice.